Introducing Doughnut Economics: putting people—not money—first

The sweet spot where all of humanity can thrive.

What on earth is Doughnut Economics?

I’ll let Kate Raworth (co-founder of Doughnut Economics Action Lab) tell you in her own words:

The problem, Raworth contends, is our addiction to growth.

The need for perpetual growth—that ever-rising line—has been so deeply ingrained in our psyches that it’s become the de facto success indicator for over 60 years.

I’m reminded of a passage from The Little Prince:

“Grown-ups love figures. When you talk to them about a new friend, they never ask questions about essential matters. They never say to you: ‘What does his voice sound like? What games does he prefer? Does he collect butterflies?’ They ask you: ‘How old is he? How many brothers does he have? How much does he weigh? How much money does his father earn?’ It is only then that they feel they know him.

If you were to mention to grown-ups: ‘I’ve seen a beautiful house built with pink bricks, with geraniums on the windowsills and doves on the roof….’ they would not be able to imagine such a house. You would have to say to them: ‘I saw a house worth a hundred thousand pounds.’ Then they would exclaim: ‘Oh! How lovely.’”

An observation that’s just as relevant today as it was when the book was written in the 1940s. Why are we so obsessed with numbers and money?

From growth addicted to growth agnostic

Capitalism has a lot to answer for, including the fact that by 2030, global poverty is estimated to reach 7 percent (around 600 million people).

Meanwhile, a recent BBC report highlights a 66% chance we’ll exceed the 1.5C global warming threshold between now and 2027.

We’re a long way from achieving the United Nations’ 2030 Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), which aim to end poverty, improve human lives, and protect the environment, by 2030.

There’s a time and place for growth, such as:

Babies, adolescents, young animals and plants

New businesses and ideas

Low- and middle-income countries where most of their population still live in poverty

All the above need growth, but just as humans, animals, and plants stop growing when they reach maturity, the same goes for the economy.

We’ve made encouraging progress with circular and sustainable business models, but as long as businesses remain primarily growth-driven, they’ll keep contributing to overconsumption.

Carbon emissions are generated not just in the production process, but throughout the entire supply chain—from the transportation of raw materials to the manufacturing process to the distribution, until the product finally arrives in the hands of the consumer. And there’s the product’s end of life to consider too.

Some companies, like Allbirds, are taking charge of sustainability innovation with their upcoming launch of the world’s first net zero carbon shoe—without carbon offsets!

Instead of just pushing consumers to buy new products, sustainable businesses should also promote circular and community initiatives such as repair and reuse, sharing services, or repurposing pre-used products.

If you’re wondering—surely a business should drive sales and not the opposite? Well, that depends on the organisation’s priorities.

What’s more important: growth and profit at all costs, or providing value that benefits the community without deepening our climate crisis?

Businesses could still achieve their financial goals while contributing to communities in need. For example, Allbirds and Zappos partner with Soles4Souls to distribute returned and unwanted shoes and clothing to those living in poverty in developing countries, which they can sell for income at their local marketplace.

Not only does this divert millions of pounds of textiles from landfills, but it also helps create economic opportunities for people in need all over the world. Just one pair of gently worn shoes will enable a mother in Haiti to provide five meals for her family.

By applying the principles of Doughnut Economics, businesses would be regenerative and distributive by design, rather than existing primarily to fuel consumption and generate profits for shareholders.

Doughnut Economics: an economic system that lets humanity thrive along with the planet

Doughnut Economics is derived from a simple but fundamental idea:

For humanity to thrive in the 21st century, we need a regenerative and distributive economy—one that’s growth agnostic.

The goal: to get all of humanity into the Doughnut’s sweet spot.

The Doughnut consists of two concentric rings:

An inner ring: the social foundation that ensures no one is deprived of life’s essentials, and

An outer ring: the ecological ceiling we must not collectively overshoot, to protect Earth’s life-supporting systems.

Between these two rings, the doughnut-shaped sweet spot allows humanity to thrive in an ecologically safe and socially just space.

As Raworth puts it:

“Instead of economies that need to grow—whether or not they make us thrive, we need economies that make us thrive—whether or not they grow.”

From Raworth’s perspective, economic growth should be a means to achieving social goals within Earth’s boundaries, rather than simply an indicator of success.

We need money to live a decent life, but how much wealth is enough? It’s a form of addiction in itself. People who hoard wealth and have millions tucked away will always want more.

Meanwhile, hundreds of millions lack access to even the most basic needs. How is this right?

We can do better. We must.

It starts with a shift in perspective.

How to think like a 21st-century economist

Raworth’s book, ‘Doughnut Economics: Seven Ways to Think Like a 21st-Century Economist’, aims to change our perspective—from the 20th century’s self-profiting economic thinking to a more open and dynamic mindset befitting our modern, complex times.

Doughnut Principles of Practice

1. Change the goal: from GDP growth to the Doughnut

Instead of endless growth, we need a far more ambitious and global economic goal for the 21st century: “to meet the needs of all within the means of the living planet”—in short, to thrive together.

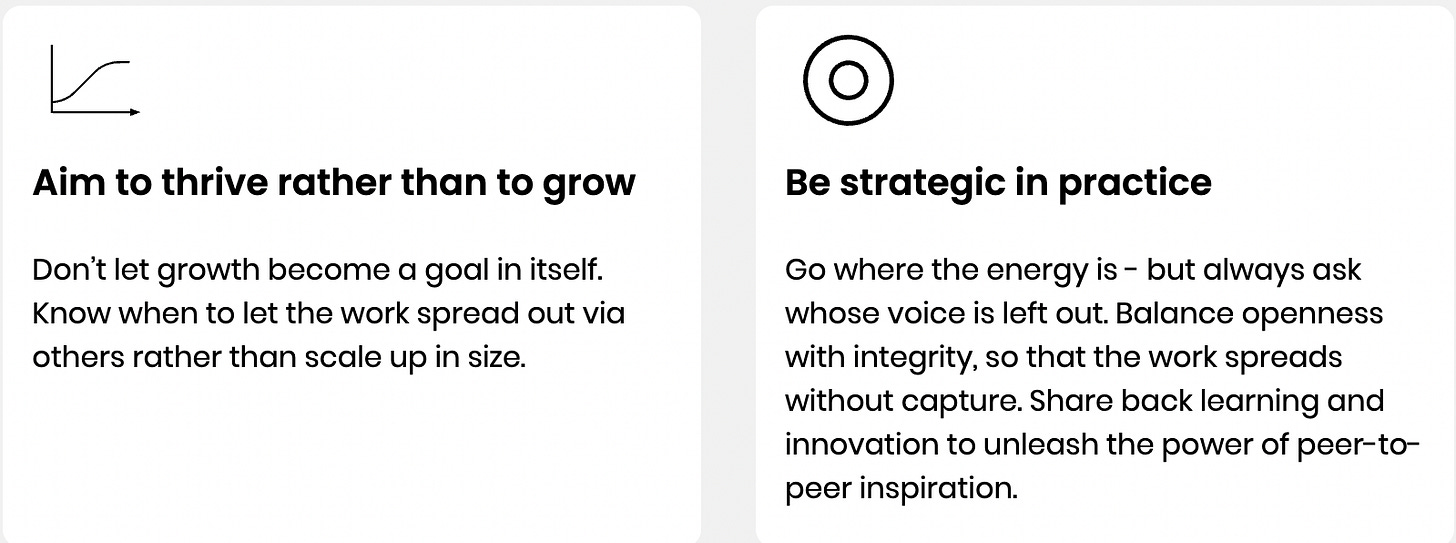

2. See the big picture: from self-contained market to embedded economy

From a free market economy—where regulation is minimal, the state’s role restricted, society deemed irrelevant, and Earth’s resources believed to be unlimited—Doughnut Economics proposes a more holistic worldview.

One where the economy is embedded within our natural environment and our human society. In this embedded economy, the market, household, state, and commons all play an equally important role in supporting human welfare.

3. Nurture human nature: from rational economic man to social, adaptable humans

The ‘rational economic man’ is the central figure in mainstream economic theory. Depicted as “standing alone, money in hand, calculator in head, ego in heart, and nature at his feet, he hates work, loves luxury, has insatiable wants, and knows the price of everything.”

With the global population predicted to reach 10 billion by 2050—if we wish to thrive together on this fragile planet—it’s time for a new portrait of humanity.

One that’s reciprocating, interdependent, and compassionate, driving a new brand of economics that nurtures the best of human nature—instead of the self-serving ‘me, me, me’ mentality.

4. Get savvy with systems: from mechanical equilibrium to dynamic complexity

Our economy is an ever-evolving system, not one that can be controlled using linear mechanical models (like the theory of market equilibrium). Instead, we need to apply systems thinking in steering the economy.

Systems thinking, as defined by Wikipedia, “is a way of making sense of the complexity of the world by looking at it in terms of wholes and relationships rather than by splitting it down into its parts.”

5. Design to distribute: from ‘growth will even it up again’ to distributive by design

Inequality is not an economic law or necessity; it’s simply a result of bad design.

21st-century economists advocate designing economies to be far more distributive of value among those directly involved in generating it. This means not just redistributing income but pre-distributing the wealth potential of the enterprise (scroll to the end for examples of distributive businesses).

6. Create to regenerate: from ‘growth will clean it up again’ to regenerative by design

As with inequality, we’ve seen that growth does not reverse the devastating effects of pollution. If anything, it merely compounds the problem.

The solution is simple: design businesses to regenerate rather than degenerate. We need a circular economy that allows Earth to flourish so that we too, can thrive.

7. Be agnostic about growth: from growth addicted to growth agnostic

It’s time to flip our perspective on growth. Instead of economies that are financially, politically, and socially addicted to growth, it’s time to explore how we can learn to live with or without it. We need economies that make us thrive—whether or not they grow.

Is the notion of Doughnut Economics so farfetched?

Sceptics have accused Raworth of “we-ism” and criticised her “unfeasibly optimistic” claims.

Is it so implausible to imagine a world where businesses, cities, and countries can all work together to create a regenerative and distributive global economy, where the focus isn’t on growing and hoarding wealth but on sharing it and taking care of Earth simultaneously?

Let us not forget that not so long ago, airplanes, self-driving cars, female Prime Ministers, same-sex marriage, and gender fluidity, were all inconceivable.

But a wise man by the name of Nelson Mandela said,

“It always seems impossible until it's done.”

So in an era of inclusivity, diversity, open platforms and social movements, maybe a revolutionary economic system that genuinely seeks to take care of humanity and protect our environment might not be so outlandish after all.

It won’t be easy; change never is, especially one of this scale. It will be tough for the masses to buy into a growth-agnostic mindset, but again, nothing’s impossible.

We just need to pitch in and do our part. As it is, businesses and cities are already stepping up to the challenge (examples below).

How to get your business into the Doughnut’s sweet spot

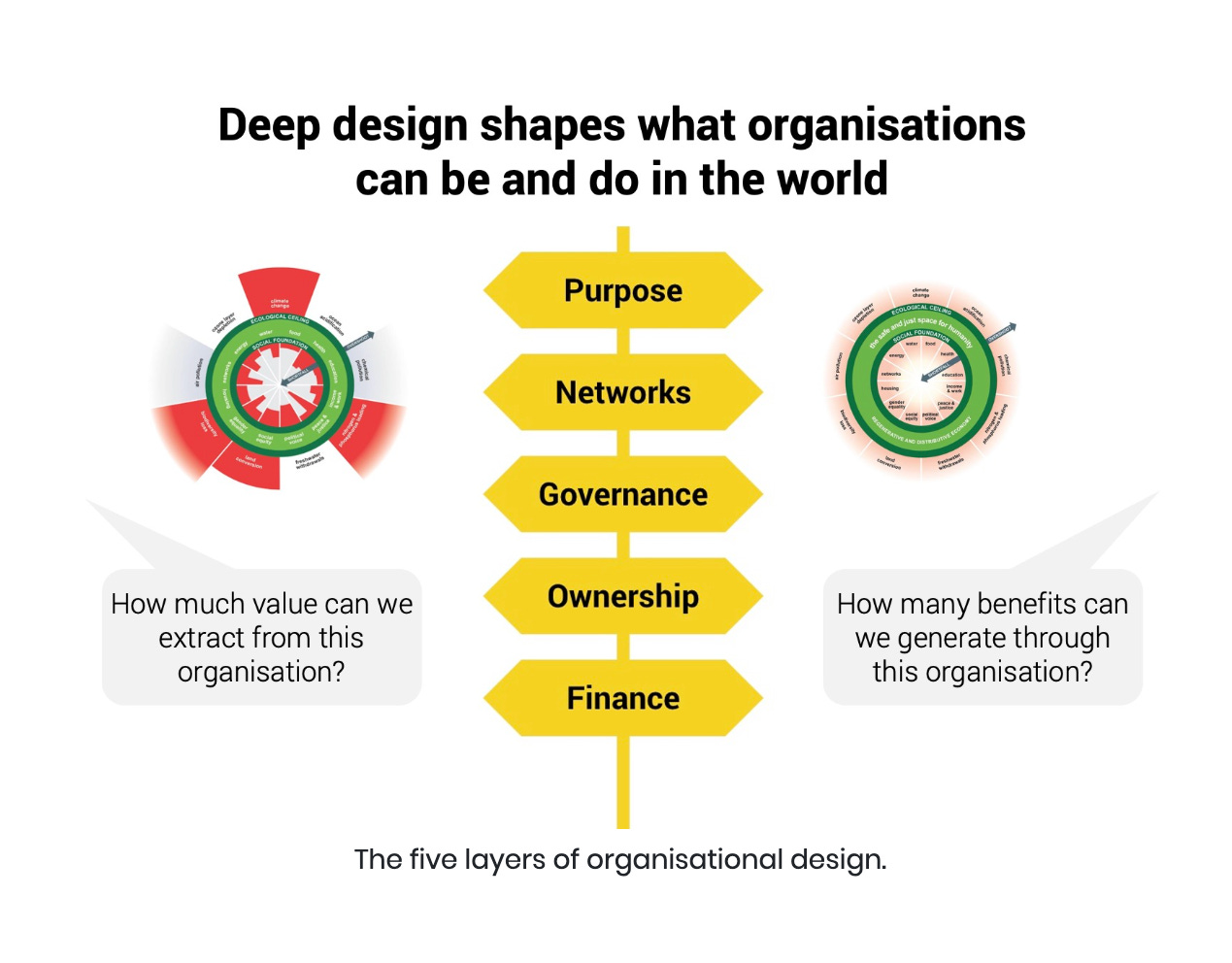

To make your business regenerative and distributive, first, you have to start with its ‘deep design’, defined by Doughnut Economics as:

The purpose of the business

How it operates in networks

How it is governed

How it is owned, and

The nature of its relationship with finance

The Doughnut pivots organisations to focus on benefit generation instead of value extraction.

Inspired by Marjorie Kelly (a leading theorist in next-generation enterprise design), these five layers of deep design are the building blocks of an organisation’s capabilities and contributions to the world.

Doughnut Economics calls on businesses to transform their deep design “to become not just ‘more sustainable’ but regenerative by design, and not just ‘more inclusive’ but distributive by design.”

“Today’s degenerative industrial systems—inherited from the last century—are still using up and running down the living world, and must rapidly be turned into regenerative industries that work with Earth’s cycles and within Earth’s means. At the same time, today’s divisive context—thanks to the concentration of ownership and power in far too few hands—must be turned into distributive outcomes, through an economy that shares value and opportunity far more equitably with all who co-create it.”—Doughnut & Enterprise Design paper

Join businesses & cities in the transformation

Examples of regenerative enterprises:

Yvon Chouinard, Patagonia founder, former owner, and current board member proclaims:

“Instead of extracting value from nature and transforming it into wealth, we are using the wealth Patagonia creates to protect the source. We’re making Earth our only shareholder. I am dead serious about saving this planet.”

This radical move brings Patagonia’s governance, ownership, and financial parameters in line with its stated purpose to “save our home planet”.

UK-based soap and haircare brand Faith In Nature formally and legally restructured the company by appointing a non-executive director to represent nature on its board, “giving the natural world a legal say in its business strategy”.

Willicroft’s ‘Make Mother Nature Your CEO Campaign’

When Willicroft’s initial life cycle analysis revealed that cashews were the highest greenhouse gas emitting ingredient in their plant-based cheese, they decided to switch to beans and pulses instead, which create ten times lower emissions (read more here).

They’re also spearheading the ‘Make Mother Nature Your CEO Campaign’ by inviting companies to join their initiative.

Examples of distributive enterprises:

Manos del Uruguay

Every piece of Manos del Uruguay’s ethically and sustainably handmade garments helps improve the quality of life of Uruguay's rural women. The artisans who create the garments co-own the company, and profits are either shared among the cooperatives or re-invested in the organisation.

Breedweer

As one of the 10% most social companies in the Netherlands, Breedweer links sustainability with creating social returns, showing that the proof is indeed in the Doughnut!

Besides implementing circular business models in its cleaning services, Breedweer proactively employs people from vulnerable target groups, and trains and develops them at the Breedweer Academy. The company also reinvests 50% of profits into activities supporting its social mission, ensuring that it creates continuous and lasting social impact.

A dairy cooperative in India, Amul’s small-scale farmers own the business, benefit from its profits, and have a say in the way the business is run.

While these businesses are still in the process of becoming fully regenerative and distributive (though Breedweer comes close), they are prime examples that transforming the deep design of business—specifically its Purpose, Networks, Governance, Ownership, and Finance—is key to unlocking the potential of business to shape a regenerative and distributive future humanity so sorely needs.

The emergence of Doughnut Economics cities

So far, Doughnut Economics has been adopted in cities such as Amsterdam, Copenhagen, Brussels, Dunedin (New Zealand), and more.

Working towards bringing their 872,000 residents into the Doughnut’s sweet spot, Amsterdam is collaborating with Raworth’s Doughnut Economics Action Lab (DEAL), introducing massive infrastructure projects, employment schemes, and new policies for government contracts to make their vision a reality.

It might seem overwhelming—the goal of meeting the needs of all within the means of the living planet. But as with all things, we need to start somewhere.

Will you join the revolution?